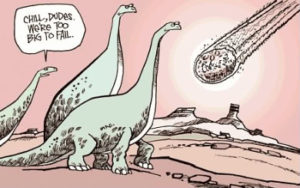

Too Big to Succeed

0 comment

People tend to look for the easy answers. For example, I’m asked all of the time, “How long should an executive director stay in her/his position?” Simple question to ask; complex question to answer, as it isn’t a functions of years (the answer folks are looking for), but rather a function of the person’s actual performance of the job, the continued interest in doing the job and the interest in, and willingness to, push the envelope in order to be the best possible and not settle for status quo.

Another question asked with the hope of an easy yes or no answer is “should we grow”? How big is too big? The answer is a function of too many individual organizational factors to list here and that question should never be answered without a lot of data collection, reflection, consideration of need, organizational capacity, leadership capacity, etc., and, of course, more thought and reflection. But I have been thinking about this question a lot since reading of yet another long-standing nonprofit closing its doors: Community Connections in Jacksonville, FL.

Founded in 1911 as a Young Women’s Christian Association, providing residences for 12 women and transient housing for nine, Community Connections was, at the time its board decided last week to close the organization, providing housing for 43 women and 35 children in dormitory-style housing. They also provided a Head Start program for the residents’ children as well as for others, plus an after school program.

According to their 2014 Form 990, they had a staff of 180 and 1,625 volunteers, quite a difference from the 45 full-time and 25 part-time employees of today. And, according to the 2014 990, 82% of their almost $5.5 million income (an increase of $500,000 over the previous year) came from government grants. Experts know that an over-reliance—51% or more—on one source of funding is a death knoll. Sadly, too many working in the sector only intellectually accept that as a truth, while few working in the sector have internalized that message enough to do anything about it. In its statement on the website about Community Connections’ closing, the board points to the two things that fueled its decision: the federal government’s shift away from supporting transitional housing and its own aging facility.

While in a different league in terms of size from Hull House (Chicago) and FEGS (New York), I could not help but think of these two predecessors—long-standing nonprofits, overly dependent upon government dollars whose boards also made the decisions to close due to “on ongoing difficulty securing revenues adequate to cover costs.” During the Great Recession we all became familiar with the phrase “too big to fail;” with nonprofits, we have to consider where there is a flip phenomenon of “too big to succeed,” where too big is completely situationally defined. When we get “too big,” do we lose the focus of our mission (which is different than the associated problem of losing focus on our mission)? If we get “too big,” do we lose the ability to continue to be community-based? Is the push for mergers, which many funders and others see as the solution for struggling nonprofits and as a way to stem the ever-growing sector, really pushing organizations closer to their demise?

The literature explaining the high rate of business failures—96% of for-profit businesses fail within 10 years of starting, and much of that happens within the first two years—is, not surprisingly, similar to many of the best practices to which all nonprofits should adhere. While not a complete list, here are some key ones which every nonprofit should consider as it ponders its own destiny and the question of “too big to succeed.”

- A diffuse, unfocused mission. Two words: kitchen sink. As nonprofits chase dollars, grabbing those just on the periphery of their missions or well beyond, they continually dilute the mission statement to the point that it cannot provide several key services: guiding decision-making and differentiating them from their competition (with the latter being another frequently cited factor leading to the demise of for-profit businesses).

- Leadership dysfunction/failure. While in the for-profit sector, this refers just to the paid leadership, in the nonprofit sector this is a failure that rests at the feet of both the paid and volunteer leadership. Too often, boards have sat back for years watching an executive director wallow in incompetency, taking the organization down in bigger or smaller steps, too lazy or unwilling to step up and do what needs to be done. In so doing, they exhibit their own dysfunction and failure, waiting too long to wake up before trying to seize the reins of a horse that is long since freed himself of the harness.

- Unprofitable/poor business model, too frequently coupled with poor financial management and oversight. Each deserves to be called out on its own as each is singularly important, but even more devastating when combined. Yes, nonprofits have business models, though too many fail to recognize this. If they did, they would see that their models are exceedingly poor and generally totally unprofitable; they are also not models that will sustain a program or organization for the long haul. To wit, a program budget, or, even worse, an organizational budget, that is disproportionately dependent upon one source of income. Add to this staff and board who either abdicate, partially or completely, their financial management and oversight responsibilities, do them only sporadically or who are in over their heads, and you absolutely have created a path to financial failure about which no one should be surprised.

- Loving the problem more than the solution. Put another way, with a quote by an unknown author: organizations “continue to explain the reality rather than confront the reality.” Failures don’t happen overnight, but rather after a long time of either ignoring the problem or, as this item references, the desire to continually massage the trauma rather than healing it.

- Failure to communicate their value proposition. It is hard to communicate your value proposition if you don’t know what that proposition is, which, sadly, is the case for too many nonprofits. Too many don’t believe that they need to formulate this value proposition, resting, instead, on the belief that because they are a nonprofit everyone will know that they do good—and that’s good enough. The real, competitive world says that isn’t good enough, at least not if you want to stay in business and, oh, let’s get wild, flourish. Instead, we must keep in contact with our clients to know what is needed today—not 10 years ago—so that our services are current and solid and our value position has credibility and merit.

- Failure to pay attention to the ever-changing world in which they operate. We ignore the world around us at our own peril. Too often, myopia limits our vision to within the confines of our own organization, while survival demands that we also constantly be looking beyond to the larger environment in which we operate. We must understand what is happening in the for-profit space, as much as the larger nonprofit space, particularly as the former creeps more into the domain of what used to be seen as strictly nonprofit.

This non-exhaustive list is not one from which you can pick a subset and be confident that your organization will survive. This list is a do all or perpetually struggle, at best, or die, at worst.

The opinions expressed in Nonprofit University Blog are those of writer and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of La Salle University or any other institution or individual.