A real working board

0 comment

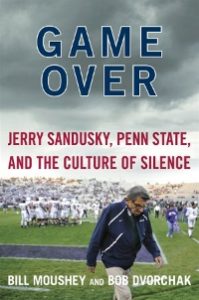

Twice a year I get to revisit the debacle that was Penn State’s board back at the time of Sandusky, as I use the Freeh Report as case study for my graduate students. Each time I reread it or discuss it, I renew my belief that I expressed the very first time that I wrote about the Freeh Report in 2012, that this should be required reading by every nonprofit board member. And, then, every board should have a thorough conversation, identifying all of the mistakes the Penn State board made, the failures in the relationship and imbalance of power between the board and the University President and how the board failed to protect and steward the mission of the organization. Sadly, though, this has not happened. Too few board members have read the report; even fewer, if any, boards have discussed it and used it as a mirror for themselves.

At some point in the class where we discuss the Freeh Report, I ask each group of students if they thought their board would read it. Eight times I’ve taught this class; eight times not one person said their board would be interested in reading it—until the other night. And then there was one, who is a board member.

Why, I asked, did he think his fellow board members might be interested? Because his organization, too, works with young people. When I have asked every other class why they didn’t think the boards of the nonprofits where they work or where they serve would not be interested in reading the Freeh Report, I get the same answer: their boards would say something to the equivalent of, “We aren’t a big university, so what could we possibly learn from it? We have nothing in common, so there is nothing that could be learned.”

Nonprofits love to tell us when they are explaining their needs for our education or consulting help that they are unique. Where this urgent need to be unique has come from, I do not know; but I do know that it stands in the way of potential success in so many arenas. It encourages a mindset that values differences above commonalities, rather than valuing both equally and being enriched by both. And it certainly prevents one nonprofit learning from another, because that other is “not like us.”

If you doubt this, just watch the headlines from around your community, state or country. See how frequently nonprofits are repeating the exact same mistakes made by other nonprofits that look nothing like them—different missions, different sizes and ages, different geographies. These different organizations all allowed for the exact same failures—the failure to have a sound internal control system or to have a balance of power between the executive director and board or to have a diversity of income streams, to mention but a few. And they all suffered the exact same consequences: negative headlines, closing their doors, lawsuits, and more. Funny how the same things can happen to a whole bunch of unique organizations.

What I should never do is follow-up my graduate evening class on the Freeh Report with a day-long, general training on nonprofit board roles and responsibilities to a group of nonprofit board members. I just made that mistake this round, and that audience paid for it.

An innocent question—that usually is made as a declarative statement—got a lot more shock and awe in my response than I usually deliver. The question asked whether the descriptor that so many like to use of being a “working board” is naming something different than being a governing board. (As I said, I usually here there as the statement that folks make as they start to make their case of being unique, “Well, we are a working board”). My usual response to the statement blew out of my mouth rather than flowing gently: Every board should be a working board! Had Penn State’s board been doing its work all along, what happened would, at best, never happened, and at worst, been stopped much earlier in its tracks, caused much less harm to innocent children, not defamed Mike McQueary, the ultimate whistleblower in the case who is now over 40, unemployed (because no one wants to hire him) and living with his parents. But the board hadn’t been working, it hadn’t been doing its job.

Let me repeat: every board should be a working board. Yes, the position of a nonprofit board member is an oxymoron—it is a volunteer job. Somewhere along the way, though, between colonial times and the birth of the predecessors of modern boards to now, board members were allowed to lose sight of the job component to that descriptor and just focus on the volunteer part. While it annoys me when board members do the volunteer whine—“Oh, but we are just volunteers,” it infuriates me when I hear executive directors and directors of development say that.

Again, somewhere along the way, people have come to misunderstand “volunteer.” Volunteering doesn’t mean being lazy; it doesn’t mean slacking off or disappearing. It doesn’t mean you get to do how much or little you feel like, or doing what is convenient for you, or doing what you want to do rather than what you must do.

Volunteer comes from the Latin, voluntas, meaning will. Thus, when we volunteer to do something, we are doing so of our own free will. And, no one should accept the position of nonprofit board member without fully understanding the job which they are, of their own free will, agreeing to do.

Sadly, though, when those who like to tell you that their board is a working board, they aren’t referring to working at the job of being a board member—the job of setting organizational direction, overseeing the money, helping to raise that money by stewarding relationships, creating policy, and more. No, they are talking about working to help implement the mission. They are talking about painting sets and teaching classes and cooking food and handling cases. They are talking about working at being surrogate staff because the organization can’t afford to hire any or enough staff.

I am not disagreeing that that is work; those of us who work at a nonprofit know that our jobs entail a tremendous amount of hard, sometimes emotionally draining, work. But that work is not the job of board members. If those board members were doing their job, ensuring that there was a solid strategic plan that would spell out organizational direction; if they were proposing solid budgets for organizational sustainability; if they were identifying and cultivating donors who would be willing to fund that budget to achieve the planned organizational direction, there would be sufficient dollars to hire real, qualified staff to do that job, allowing board members to do their job—and govern.

Penn State’s board was not governing; it was allowing the paid head of the organization to act as if he were the top of the organizational chart instead of the reality that the board was; it was not ensuring that policies were in place and that the top staff leader had a mechanism in place to confirm compliance; it was not keeping the mission—education—front and center; it was not asking for data it should have been, nor asking the questions it should have been; and this list could go on. These are common mistakes that too many boards make, day in and day out. There is nothing unique about them, or Penn State, or your own organization. Board members: wake up and recognize the risk of not doing your job!

The opinions expressed in Nonprofit University Blog are those of writer and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of La Salle University or any other institution or individual.