Time to Brew the Tea

2 comments

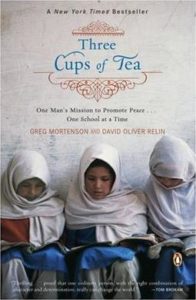

When it comes to reading, I often come intentionally late to the party. I figure if everyone else is talking about it, I don’t need to be reading it right then as the word is getting out. Which is why I find myself now, five years after its publication, reading Three Cups of Tea. It is, as everyone said, a nice read—at least as far as I’ve gotten.

There are many things that one can take away from this book and Greg Mortenson’s story; the one that has me currently thinking might seem inconsequential. It is the serendipitous path (no pun intended, but those of you who have read the book know that it was losing the path that landed him in Korphe) that turned him from mountain climber to philanthropist.

I have, for a long time, wanted to bottle that thing that makes some people philanthropists while leaving others behind. And to be clear, the definition of philanthropist in my book does not rest on how much you give, but rather that you give—be it time and/or money—on a regular and consistent basis. Why do some people make philanthropy a central part of their life, while others barely give it a nod and still others ignore it completely?

There is no doubt that growing up in a philanthropic family is a key factor in creating future philanthropists. Research tells us that. And Greg Mortenson had that example. His parents were responsible for building the first teaching hospital in Tanzania when he was growing up there. He witnessed the power of philanthropy first hand.

And yet it wasn’t until he stumbled into the remote village of Korphe, Pakistan, whose people took him in and nurtured him back to good health, that he, himself, became a philanthropist. Impressed by the group of students who sat in the open air and practiced their studies, most doing so in the dirt with sticks, and despite the absence of a teacher, that he knew he wanted to build a school for Korphe, and specifically a school where more than just four girls attended. But had he been on the path he was supposed to be on, had he not gotten separated from his guide, might he not have become a philanthropist?

And now I learn that there are serious suspicions that Mortenson’s story is fabricated. He didn’t stumble, lost and confused, into Korphe; there was no nurturing him back to health. There was, instead, an intentional visit by a healthy Mortenson to Korphe sometime later; a school was built. It made for a nice story; it sold a lot of books. But if true, does it change the fact of Mortenson as philanthropist?

Does it matter that he fabricated a story that pulled sufficiently at people’s heartstrings that they gave money to his cause to build schools throughout Pakistan, with a particular emphasis on educating girls? The suggestion that he has mismanaged and misappropriated funds, if true, absolutely does matter, but that is not the question here. The question here is whether there is a right or wrong path to becoming a philanthropist? Is there good and bad philanthropic money? Boards of directors often laugh at me when I say they need a gift acceptance policy (see “Dirty Money post,” 3/11/11) that is about more than just what kinds of gifts their organizations will accept—stocks, bonds, property, art, cash only? The idea that gifts might be turned down because of the stock in trade, the ethics, the morality of the donor seems funny to most. Why, when funds are so tight, would we turn a gift away?

Philanthropists don’t have a lock on moral and ethical behavior just because they want to do good with their time and/or their dollars. The motivators for doing that good vary greatly: some do it just to do good, others do it for self-aggrandizement; still others do it for a combination of reasons.

Are there right and wrong kinds of philanthropists? And if so, how do we leave the replenishment of “the right kind of” philanthropists to chance?

The opinions expressed in Nonprofit University Blog are those of writer and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of La Salle University or any other institution or individual.