Nonprofits Rebel!

0 comment

Even after decades, whenever a client learns that my doctorate is in criminology, there’s always a comment and I’ve heard them all. A common one is: “There are a lot of criminals in nonprofits,” followed closely by, “Give me some time and I’ll figure out the connection.”

The move away from criminology—it has been a good 15 years since I taught my last criminal justice class—to immersing myself in the broader world of all nonprofits—was not gradual. One day I was a full-time criminal justice professor and the next I was teaching one class and spending the rest of my time working with nonprofits, doing research, evaluations, designing programs, etc. Within another year, the one class had disappeared and I was running The Nonprofit Center, fully immersed in “the sector” and teaching a class in nonprofit management in the MBA program. But, while I left teaching criminology behind, I did not leave that knowledge behind. Periodically, something from my past world moves does move over into my present, and the connection is definitely made.

I had that experience the other night as I was reading students’ posts on the discussion board in the on-line governance class in our Masters in Nonprofit Leadership program. I had asked students to describe and comment on any “five monkeys” scenarios that they had witnessed or experienced with their board and/or organization. (While you can find many different explanations of the five monkeys experiment, the best, just because of the story teller, is Eddie Obeng’s rendition in his keynote address to JiveWorld13. More sedate renditions can be found elsewhere on the web.

The five monkeys is an experiment that shows how we learn to become complacent and do things the way they have always been done. Post after post on this discussion board had examples of boards doing just that and, in so doing, not doing anything remotely what they should have been doing. As I was reading all of these posts, with my current “nonprofit sector frustration of the month” (which is how we so easily accept mediocrity as “good enough”) as background, I was reminded of Robert Merton’s strain theory.

Merton, one of the great American sociologists, developed strain theory back in 1938 to explain why some people became criminals while others did not. He postulated that the acquisition of money was a goal shared by most Americans. Unfortunately, however, he noted that while everyone aspired to the same end, the legitimate means to access that end was not equally available to all. So, he said, people adapt, and he identified five different modes of adaptation to wanting the socially sanctioned goal of money while not having access to the socially sanctioned means to achieve the end. I see those five modes of adaptation in board members who don’t know what it is they are supposed to do but know they are supposed to be doing something.

According to Merton, the most common mode of adaptation is conformity. With conformity, people accept both the socially sanctioned means and the ends. They use education, employment, hard work, etc., to get wealth. While conformity is not nearly as common among nonprofit board members as it is among our general population, it exists, but not as the dominant mode of adaptation. These are the board members who understand what the socially sanctioned goals are of a nonprofit board and seek the socially sanctioned means—training, peer learning, conferences, reading—to achieve those goals.

Another mode of adaptation that Merton describes is ritualism. With ritualism, people choose the socially sanctioned means available to them and moderate the expectations of success. So, no great wealth, but enough to do okay. In the board room, this comes down to where we see so many boards operating—in Richard Chait’s (et. al.) fiduciary mode. These are the board members that provide just the basics—the oversight, the check lists, making sure the rules are adhered to, the laws followed, all to get to the next day. They have selected a socially sanctioned means to just get by; it is better than nothing. They are not striving, sticking with Chait and his colleagues, to get to either the strategic or generative level of governance; they are happy and content with the basics.

The third method of adaptation is retreatism, and we see too much of this in our board rooms. Here, an individual rejects both the socially sanctioned means and desired ends and, as is often said, finds “a way to escape.” Sadly, we see this behavior all too often in boards that have abdicated their roles and responsibilities to the executive directors and found their escape in being rubber stamps. They aren’t present or engaged at board meetings, they don’t support events, they don’t share contacts, etc. They haven’t bought into the desired end of being an oversight body, of providing direction, of sharing leadership with executive directors. And they certainly haven’t bought into the means—by which I mean even a little of the work, which, at least, the ritualistic boards do.

Innovation is, according to Merton, the mode of adaptation that produces crime. In this mode, the socially sanctioned means of wealth has been fully accepted. The socially sanctioned means, however, are not available, and so folks innovate—producing burglars and robbers, white collar criminals and proffers of Ponzi schemes. These are people who bypass nonprofit boards, and seek their fame and glory or opportunity to give back and make a difference and use the means of running for elected office. But you can see individual board members selecting innovation as their personal mode of adaptation as they seek to become board presidents and dictate the show, assuming that board presidents have more power than the other board members, the dominant voice over everyone else (including the executive director) and have the final say.

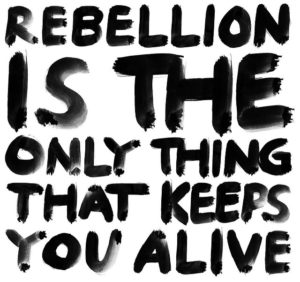

The last mode of adaptation is rebellion, my personal favorite. These are the folks who reject both the socially sanctioned means and ends and work to replace them. Think of the movements of the 1960s and you get a sense of rebellion. With the exception of those who have opted to pursue John Carver’s model of governance—which changed up both the desired ends and means—we haven’t seen much rebellion in the nonprofit board room.

Are we wasting resources trying to bring conforming boards further along the best practices continuum, pushing ritualistic boards to stretch and move to strategic and generative modes, shaking retreatist boards loose from the grip of an overbearing executive director? Maybe what we really need is to rebel until we find an alternative model(s) that really works.

The opinions expressed in Nonprofit University Blog are those of writer and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of La Salle University or any other institution or individual.