The Nonprofit Hippocratic Oath

0 comment

A headline in a recent Kellogg Insight grabbed me, in part because of the many conversations I’ve had of late, and partly because it is a question that, in various forms, I am constantly trying to get nonprofit staff and boards to ask of themselves.

The headline reads: “Why Well-Meaning NGOs Often Do More Harm Than Good.” The variations on this theme that I ask of staff and boards go something like this: Should a nonprofit that does more harm than good continue to be supported and “allowed” to operate? Whose definition of harm and good are we using anyway, in that situation? Should a nonprofit that does neither harm nor good—in other words, one that doesn’t move the needle in any direction—continue to be supported and allowed to do its thing? And, the biggie, of course: is our mission still needed?

One of the most idiotic and harmful mindsets—held by far too many working in and supporting the nonprofit sector—is another variation on a theme. The original theme is cogito ergo sum; I think, therefore I am. For too many, the nonprofit equivalent is: ego nonprofit; itaque ego bonus sum, et digna est. I am a nonprofit, therefore I am good and deserve to exist. And because I am a nonprofit and, therefore, deserve to exist, people shouldn’t question my existence, including, but especially, my own staff and board. Moreover, I should not be asked to prove the goodness of the work I do.

I cannot help but think of Andrew Carnegie. Why don’t people pay more attention to people’s names? Carnegie always seems to inspire strong feelings, be they love or hatred. Dislike is easily fueled in part by a misinterpretation of his thinking and, in part, by using today’s lens to interpret his thinking.

The Gospel of Wealth is Carnegie’s 1889 explanation of his view of the philanthropic responsibilities of the wealthy. A blunt man, he did not countenance those who, in his mind, wasted their philanthropic efforts on programs that seemed to perpetuate problems rather than solve them. In other words, he was not a fan of putting band aids on problems when the band aids could easily come off. He wanted to address root causes. Salvos seemed to believe, at best did not move the needle and, at worse, did harm.

During this pandemic, as many nonprofits are struggling to stay afloat, is the perfect time for board and staff to be asking tough questions. Just because a nonprofit can survive—be it only barely—does not mean it should. Is it contributing enough measurable and real good to warrant its survival, as opposed to surviving simply to perpetuate what someone started or someone’s legacy, or to safeguard employee’s jobs, etc.

PPP allowed businesses of all types to keep their employees on the payroll for eight weeks on the assumption that those employees were doing necessary work. Is work that does not deliver on what it promises—such as improved employment success, moving out of poverty, recovering from addiction, understanding of other cultures, resettlement, better academic performance, cleaner air and water, etc., essential? Wasteful? Or, even worse, harmful?

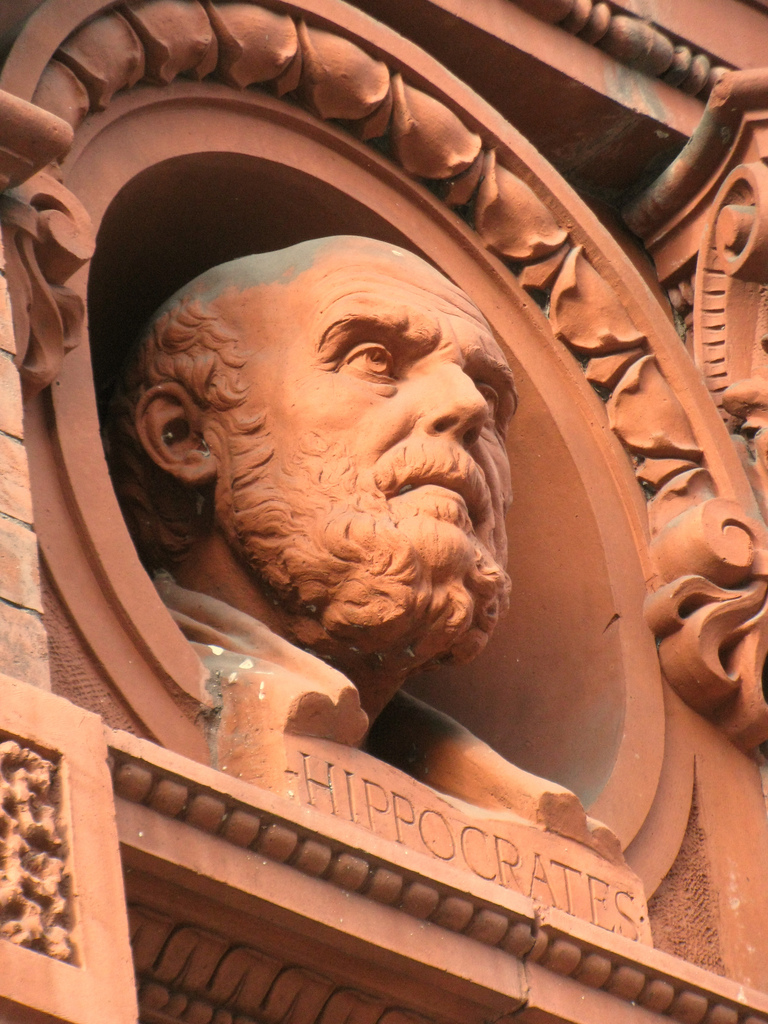

Perhaps it is time for a Hippocratic Oath for our own sector? After all, why should doctors be the only ones charged with the admonition to “do no harm?” If we are to be true to our sector’s charge—to work on behalf of some portion of the public good—then we must promise to do no harm while trying to do good. In so doing, we must be able to clearly describe what our harm would look like. And if we promise to do something, then how can the failure to do it not be perceived as causing harm?

The opinions expressed in Nonprofit University Blog are those of writer and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of La Salle University or any other institution or individual.