Letting Employees Soar

0 comment

One of the hallmarks of a profession is that it has its own unique body of knowledge. Sometimes the unique body of knowledge of one profession butts up against the unique body of knowledge of another, and then what do you do?

For example, the unique body of legal knowledge tells board members one thing about doing work with a board member’s company (that is: so long as the board member disclosed the conflict of interest and her/his fellow board members knew of the disclosure, her/his fellow board members may elect to do business with his company), while the unique body of knowledge of nonprofit professionals tells board members another (that is: best practices is that you simply do not do business with a board member’s company -period). Your choice: legal or best practices.

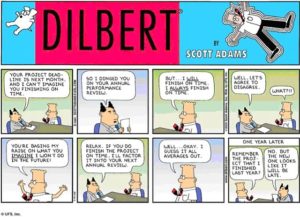

I could not help but think about this clash as I attended through a training for supervisors on the new performance management program being rolled out by the university where I work. This is no slight on the individuals doing the training; rather, it is a commentary on the clash between HR—(now often called talent management), and practicing management and leadership. One of the first things anyone in a position of management should learn, and any good practitioner will tell you, is that one size will never fit all. Performance management, therefore, should never be designed with the thought that the same system will work for every tier of your organizational chart.

But perhaps my greatest beef with performance management is that it yanks the rug out from under the concept of professional. To a very great extent, I blame our educational system for this. From a relatively early age, I chaffed at grades. It wasn’t because I didn’t get good grades; I did. My parents’ bar was set at the highest—we were expected to learn as much and as well as we possibly could.

But in school, that wasn’t what was prized; what was prized was the letter grade. Right after taking a test, the question asked by friends and classmates was always, “do you think you got an A?” They didn’t ask, “do you feel confident that you knew the information to answer the questions correctly?” As soon as a test was handed back, or report cards were distributed, my friends and classmates pounced on one another and asked, “what did you get?” They didn’t ask “how much did you learn correctly?” That wasn’t important; what was important was how well someone else, in this case, the teacher, told you you were doing. Our education system has not taught people how to create their own standards and how to evaluate their own performance, it has made them dependent on others to tell us how well we are doing—or not doing.

Workplace performance management picks up where school left off. For too many, it replaces the teacher with the supervisor. It is now the supervisor who, ultimately, tells the employees how well they are doing. Apparently, we have created generations of people who, despite being given a job description, being told the rules of the game (organizational values, work hours, dress code, proper decorum, etc.) cannot determine on their own whether they are doing okay, “well enough,” exceptionally. But, wait! No one, according to the talent management experts, is allowed to be exceptional all of the time. You were allowed to get straight As in school and be told that you were, in fact, exceptional, all around. But get to the workplace, and no matter how well you live up to your job responsibilities, exemplify organizational values, follow all the dos and don’ts of the workplace, you are not allowed to get straight As.

But what if you have hired exceptional talent, and done what so many successful leaders say they do—hire people smarter than you and then get out of their way? (And when you make a mistake in a hire, which we all do, you cull that person from the team.) What if you hire people who are as driven as you, as committed to the mission as you, as clear about their standards of excellence as you—and only excellence will do—may they be exceptional? Do those people really need to go through a forced process of annual self-evaluation and then with their supervisor a forced annual process of grading? Don’t true professionals do continual self-assessment, and the relationships professionals have with their professional supervisors provide the outlets for continual feedback?

I freely admit I am a lousy supervisor; I have no interest in telling people where and how I think they should be doing better. That is their job. (I’m more than happy to help in any way I can if there is anything they think I can do to help them do better. But I absolutely do not want to foster anything that smacks of dependency on me for how they feel they are doing at their jobs. Again, it is their job to determine how well they are doing.) I do, however, have an interest in setting a workplace culture that expects exceptional performance from everyone, providing the supports they need to be exceptional, and then getting out of the way. The professionals will soar; the others, not so much. And the latter will be those that go.

So, tell me again why anyone needs to spend time doing performance management with professionals?

The opinions expressed in Nonprofit University Blog are those of writer and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of La Salle University or any other institution or individual.