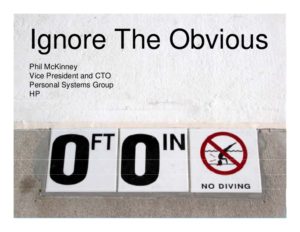

Ignoring the Obvious

0 comment

Willful blindness. I have always loved this term—far more descriptive than some of its legal synonyms: ignorance of the law, willful ignorance, contrived ignorance. No, this says it all: a person glanced, didn’t like what s/he saw, so s/he suddenly becomes blind and can no longer see the behavior or the suggestions of that wrongdoing.

Earlier this week, a parliamentary committee investigating the wire tapping scandal at Rupert Murdoch’s media empire said that Murdoch was “not a fit person to exercise the stewardship of a major international company” because of his willful blindness to the pervasive phone hacking used by his media team. Using this standard criminal law concept that describes behavior whereby a person intentionally avoids knowing things that could make him/her criminally liable (such as the drug runner who couriers a package but does not directly ask, “Are these drugs I’m carrying?”), the parliamentary commission is saying that Murdoch intentionally turned a blind eye to things that he suspected, thought, wondered were criminal, not pursuing the truth, but preferring to pretend “not to know.”

Unfortunately, that old adage, “what you don’t know can’t hurt you” is far from wise. That drug runner who believes he can go into a court of law and claim innocence by offering up the defense “I didn’t know the parcel contained drugs” has a rude awakening coming to him/her—and will have lots of down time in his/her future to contemplate that mistaken thinking. The truth is, what you think you know, even if you don’t confirm it, can hurt you if your suspicions are that bad, harmful or criminal behavior is occurring on your watch.

Listening to this report, I could not help but think about all of the willful blindness that goes on in nonprofits: by executive directors, supervisors, board members. To wit, the conversation I recently had with a lawyer friend whose client “just realized” (my quote marks, not his) that the executive director had been “misdirecting” funds for the last 10 years. Apparently, some of the board members tried to put the blame on the auditor’s shoulders, wondering how come the auditor hadn’t caught this misdirection some time ago.

It is amazing how people in positions of authority—such as executive director and nonprofit board member—do not understand how an audit works. An audit is built on the data an organization/individual provides to the auditor: provide false data and you simply get an audit of that false picture. Sometimes audits do reveal wrongdoing; but that is not the intent of an audit. The Alliance for Nonprofit Management defines an audit as “…a process for testing the accuracy and completeness of information presented in an organization’s financial statements. This testing process enables an independent certified public accountant (CPA) to issue what is referred to as an opinion on how fairly the agency’s financial statements represent its financial position and whether they comply with generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP).” It is the board’s job to be regularly monitoring those financial statements to see what is really going on. Ah, the joys of willful blindness. That is, until the shoe drops and the concept of complicity (ethical and moral responsibility, not legal, so, back off lawyers) rears its head.

How many executive directors really know how the employees in their organizations are executing their duties? Sadly, children dying in foster care is becoming too common place”to think that there is not something wrong with a system that allows that to happen. There isn’t a person, from the bottom of an organizational chart to the top of that chart who works in a nonprofit where employees—call them case managers, advisors, SCOH workers, whatever—have a responsibility to oversee a specified number of clients who doesn’t know that the number of clients per employee is well beyond what one individual can handle responsibly. Which means every executive director of such an organization is complicit in allowing a system to continue that can’t possibly guarantee the promises the organization makes. Willful blindness. The board, too, which should be receiving regular reports and outcome studies, knows, as well. The willfully blind leading the willfully blind.

The executive director who, and board which, allow the organization to chase money instead of mission in order to keep the organization afloat? The board which allows an underperforming executive director to stay on three, five, 10 years? The executive director who puts up excuse after excuse for an underperforming employee? Board members who don’t hold one another accountable for their fundraising responsibilities, their financial oversight responsibilities or simply attending meetings? My list could go on and on, as could yours. All preferring to look the other way than make the effort and expend the time to correct these deleterious practices, practices that can in the long and/or short run harm the organization and the ability to deliver mission. Willful blindness.

In May 2011, the Supreme Court decided the case of Global-Tech Appliances, Inc. v. SEB S.A., a civil patent infringement case. Obviously, the material substance of this case has little to do with most nonprofits. In its decision, the Court helped everyone who wishes to lead a legal, moral and ethical life understand willful blindness and the extent to which a court of law might exonerate a person who claims s/he did not know about—that is, willful blindness–the criminal conduct under question. The Court reached the conclusion that “a willfully blind defendant is one who takes deliberate actions to avoid confirming a high probability of wrongdoing and who can almost be said to have actually known the critical facts.”

The art of “it isn’t really there if I don’t acknowledge it out loud” is well-perfected in too many nonprofit organizations and at multiple levels of their leadership. We could try and convene a Parliamentary Commission to declare, in headlines around the world, that too many volunteer and paid leaders of United States’ nonprofits are unfit to lead these organizations. Or, we could take a deep breath, be honest with ourselves and our organizations, stop avoiding and take deliberate and swift corrective action. Fortunately for the nonprofit sector, willful blindness is easily corrected.

The opinions expressed in Nonprofit University Blog are those of writer and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of La Salle University or any other institution or individual.