No Way to Treat a Partner

2 comments

The truth is, philanthropy doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It exists in partnership. Is a person a philanthropist if there is no organization to which to give? And yet, I shudder every time I hear someone from a nonprofit tell me about some horrendous experience with a funder.

Recently, I heard of a funder who, knowing that some of the functions on its on-line application for a three year grant were, in fact, malfunctioning, never told the applicants. Instead, applicants wasted hour upon hour as the deadline steadily approached thinking they were doing something wrong, and only they were having this problem, only to finally reach out to the funder and expose their ineptitude, to be told, “Oh, yes, we know. Don’t worry; it will print out fine here.” Excuse me? This is an every-three year grant cycle on which much is hanging for every applicant. The application, even without any glitches, keeps executive directors and development folk up at night, sweating mightily, continuous gnashing of teeth, etc. And now you want that applicant to take your word that the application she is seeing on her screen, which comes off her printer, will somehow look different when it comes off your printer? How should we describe that funder: Cavalier. Insensitive. Unbelievable. But, then, it starts: excuses and understanding. They’ve done good work in the past. They’ve been through a lot of turmoil. They are really tired. In fact, there is, dare I say it, forgiveness.

All the while, I’m asking: is this anyway to treat a partner? Yes, it is should be a partnership between funder and grantee, not a prince and his whipping boy. Again and again, and more and more in recent times, I hear the complaint from executive directors and development directors (the two positions that have the most frequent interaction with funders), of how difficult the nonprofit/funder duality has become, how “It isn’t like it used to be!”

Recently, I observed a conversation where an executive director of 20 years was describing the old relationship of nonprofit and funder to an executive director of less than five years tenure. The senior executive director talked of meetings with funders where they would discuss, as collaborators, several ideas to see which seemed the best fit with the nonprofit’s needs and goals and the funder’s interests. There was the feeling, “back then,” of mutual respect, a deference to the knowledge and experience of those “work on the front lines” and a desire to find a mutually agreeable solution. The junior executive director said she’d heard such tales before, but that hadn’t been her experience. Instead, she has found what seems to have become the norm in the last 10 years: the funder—removed from practice, often served only by academics’ data (and not only is there nothing wrong with academics’ data, we are all well served by it—in relation to the reality those “in the field” know) and philosophical musing—dictates what is worth funding or not, without conversation with those who have devoted their lives to working on and in the problems.

This new system seems successful to many, only because too many nonprofits have pandered to these funders and, in so doing, forsaken their missions and, in turn, their clients. Are we that afraid of funders? And the answer, plain and simple, appears to be yes.

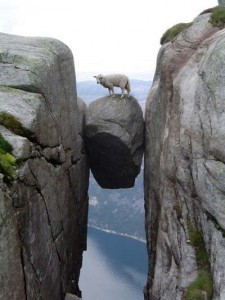

From too many nonprofit executive directors’ perspective, funders have nonprofits between a rock and a hard place: they are damned if the stay focused on mission and don’t try to squeeze their round peg into the funders’ square holes and damned if they relinquish mission to chase funders’ current dollars. From the perspective of the nonprofits, failure to play by the funders’ rules means the possibility of extinction. So they choose to stray from mission in order to get funder dollars while trying to cobble together any ways and means to continue those few programs that actually serve mission. Those few programs that actually serve the real needs of that portion of the public on whose behalf the organization was intended and supposed to work.

Does this sound like the path to creating healthy, vibrant, sustainable communities for all? In our society, there is, sadly, such widespread acceptance of the false equation money=smart, that we presume that anyone with money knows best. Money simply means money. Years in the field, years working in the problem and on the problem, means knowledge, understanding, awareness. The current paradigm of allowing the money to dictate the solutions while those who have their hands in the dirt are closed out of the determination process puts us all at risk.

Both sides are to blame for where we are: funders flexed their muscles and nonprofits allowed themselves to be cowed. Nonprofits were more concerned with survival, regardless of what that looked like, funders liked their new found egos and power and the notion of true partnerships died. And we are all suffering.

The opinions expressed in Nonprofit University Blog are those of writer and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of La Salle University or any other institution or individual.